General David Petraeus, the leader of the U.S. Army during the Iraq War and director of the CIA for a short time during the Obama administration, has had to overcome many of the challenges CFOs face when building their careers. While he now serves as a partner at global investment firm KKR and is chairman of its Global Institute, his ability to lead people, make critical decisions, develop trust and handle critically sensitive information are all skills that are not only critical for those in positions like him, but are essential for CFOs looking to expand their role outside of the finance and accounting functions of the business.

In an interview with CFO.com, Petraeus candidly spoke about the differences between the word strategic in a military and business context, how to uphold the duties of a demanding role while also being a good father, how CFOs can stay akin to the geopolitical impacts on their business and more.

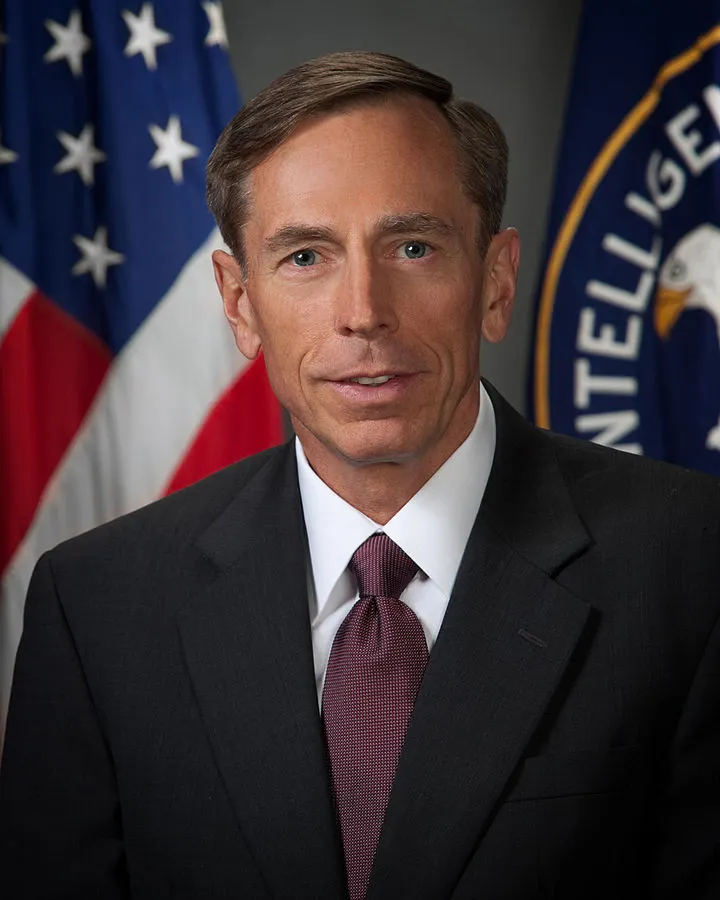

Retired General David Petraeus

Current position: Partner at KKR and chairman of KKR Global Institute

Notable previous positions:

- Director of the Central Intelligence Agency

- Commander of International Security Assistance Force

- Commander of United States Central Command

- Commander of United States Forces, Afghanistan

- Commander of International Forces, Iraq

- General of the United States Army

This interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

ADAM ZAKI: Nowadays, more CFOs say they want to be strategic. When you hear this term, how does it differ in the context of military and intelligence versus business?

DAVID PETRAEUS: I don’t think it is all that different. Being strategic is trying to understand the overall context in which you’re operating in, and understand the implications that your actions have on the organization, and for CFOs, it’s to understand the implications of your responsibilities on the business. Being aware of the tasks you are paid to perform, and having an appreciation of what that impact is and what you require to do.

In both senses of the term, it’s asking yourself how you need to adjust the big ideas of the business, do the particular functions you’re tasked with, what do they need to be successful and how your strategy needs to evolve to accomplish your goal. You must also be able to communicate the breadth and depth of the organization and oversee the implementation of the strategy so you can refine within the constantly developing understanding of the context in which you are operating.

Either personally or professionally, what types of traits or characteristics in a person indicate they are trustworthy?

PETRAEUS: I look at a number of different qualities when it comes to trust. First, there are brains. To be trustworthy you have to be intelligent, but I think there’s an element of sincerity in there as well, leveling honestly across the board, and doing it in a way that is principled, reasoned and respectful. This process, over time, can evolve a relationship that sees trust grow.

Once you begin to trust someone, their word is their bond. Their commitments must be taken as legitimate. There can be no duplicity there. There is no fudging stuff for you so you can do it for me later. Those who are straightforward earn trust in that regard. Of course, it’s a two-way street and the relationship evolves over time, but if you don’t have the crucial quality of straightforwardness within communication, you’ve got a problem. That can be a challenge in general, but if you lose confidence in someone’s trustworthiness, you may be better off replacing them pretty quickly.

So if you lose the trust of someone, is it possible to regain it back to the place where it once was?

PETRAEUS: Yes, in some situations. If it is done sufficiently, and the way that is done is through the acknowledgment of mistakes and making amends in whatever way possible. This can create a learning opportunity that some individuals can build off of. But to go forward, it’s important that the person who lost their trustworthiness in the eyes of their peers get up off the ground, dust themselves off, get their rucksack up and put one foot in front of the other in the right direction.

Everyone makes mistakes, but what we want to avoid is non-biodegradable mistakes that never go away. If that person can demonstrate multiple times they have learned from their mistake, there is a good possibility trust can be regained and a good, productive relationship can be had going forward.

For a CFO who is concerned about the geopolitical impacts on their business but is worried about the reliability of information from mainstream media, what advice or resources would you recommend?

PETRAEUS: I would recommend that CFOs focus strongly on their due diligence processes and the particular geopolitical risks they believe will impact their business. Being able to mitigate risks sufficiently so they won’t inhibit a successful outcome is crucial.

In my current role, we have a global macroeconomic analysis team. But, for business leaders who can’t develop that sort of team, they must develop their own sets of “feeds,” a term we use in the intelligence world when it comes to information.

A great resource I use is from the CIA — their unclassified news clipping service that they send out every day. They send it to me because they extend it to former directors and other senior leaders at the agency, and it’s really good. It goes out very early in the day.

I am a big fan of podcasts and go to the Economist Intelligence podcast every single day. The New York Times has also had some podcasts with relevant subjects. I think the mainstream outlets work very hard to report objectively, but you have to understand the opinions of the writers and their perspectives, which is very important. I also enjoy consuming my news while multitasking, like when I am working out. I have grown to enjoy taking in my news in an audio format.

The truth is, it would be great if we taught how to be sophisticated consumers of information early on in schools. But, many get locked into one news channel or social media silos which reinforce one set of thinking. I believe that can be very problematic.

Work-life balance had to be incredibly difficult for you. While I know it hasn’t been perfect, how were you able to develop an incredible career and meet the demands bestowed upon you by your country in the positions you’ve worked in, while also being a good father to your children?

PETRAEUS: All of the credit goes to my wife. She gave up her career to travel the world with me. We had 23 to 24 moves throughout my 37-year career. I was gone for the bulk of my final decades in uniform with six consecutive commands, five of which were in combat. I spent a year in Bosnia, four years in Iraq, a year in Afghanistan and then a year in central command where I was out in that region. And then when I worked in the CIA I traveled a lot as well.

I’ve always said work-life balance is an explicit or implicit contact between you, your spouse and your family. I happen to have an extraordinary wife, and after the kids were out of the house, she built out her career as a leader at the Better Business Bureau and the Office of Military and Veterans Affairs.

I was once asked this question about work-life balance by a cadet in a big session where I was impressing on them how important it was to be serious about what they were doing. I came home from my first tour and said I have to talk to the cadets because they’re about to behold the most extraordinary responsibility in life, the lives of our men and women in uniform during combat, and there is no place in that responsibility to be too cool for school.

The cadet stood up and asked, “Sir, how would you assess the state of balance in your life after being gone for a year, knowing you’ll likely be gone for many years in the future?” And I had never been asked that sort of question. It made me think, and in my case, I am so lucky to have a spouse who is extraordinary in shouldering my duties as well as her own. She was tolerant of some of my own mistakes too, so I don’t know how you exactly guarantee this balance. But now that both spouses in families have careers in most cases, which was much different back when I got married over 50 years ago, I believe the path my family took would be much more difficult to take today.